Lake Tahoe’s historic importance and current significance can be measured and marked in many ways, most of which center on this exceptionally pristine, abundant ecosystem. This rich history is part of what makes Lake Tahoe’s protection and restoration immeasurably important to so many. For local communities, the states of Nevada and California, and for visitors and conservationists from around the globe, Lake Tahoe is more than Jewel of the Sierra—it is a place of legend, beauty and the future of environmentalism.

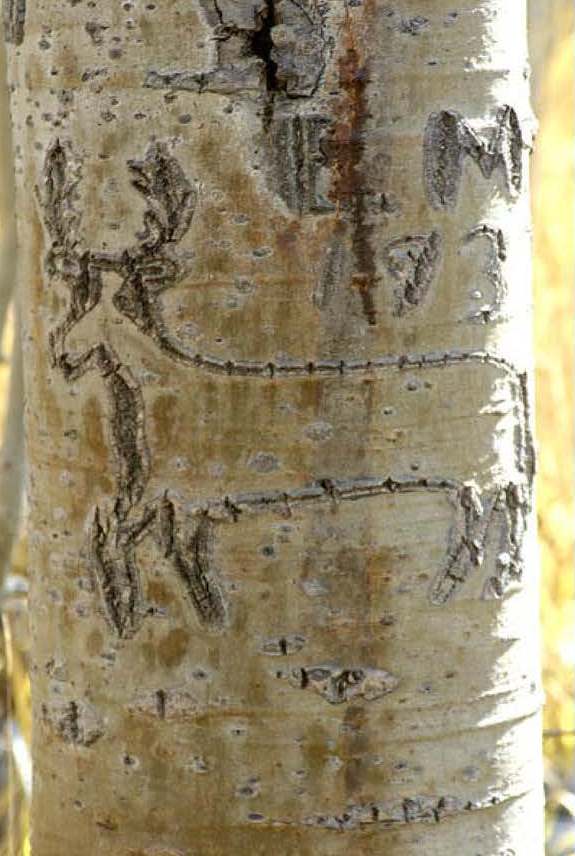

Near Pyramid Lake, where Tahoe’s Truckee River reaches its terminus today, radio-carbon dating recently revealed that a human mummy nicknamed “Spirit Cave Man” is more than 9,500 years old (three times the age of the King Tut mummy in Egypt). Similarly, petroglyphs in the area have been dated to 14,800 years–making them by far the oldest petroglyphs yet to be discovered in North America. This means humans have inhabited the wider Tahoe Region since the end of the last Ice Age—an era when saber-toothed tigers and wooly mammoths once roamed what is now Nevada desert. Beside the shores of Lake Tahoe, human artifacts 6,000 years old have routinely been unearthed at Kings Beach. Meanwhile fossilized remains of 6000-year-old submerged tree trunks near South Shore stand witness to a prolonged period of catastrophic drought. For the next 6,000 years, ancestors of today’s Washoe and Paiute Tribes found a rich source of protein in Tahoe’s famous Lahontan cutthroat trout, once celebrated as the largest in America, and deliberately set small seasonal forest fires not unlike the “controlled burns” used by the Forest Service today.

Although Spanish explorers had first reached the coasts of North America more than 300 years earlier, it was not until 1844 that the American explorer and adventurer John Fremont finally put Lake Tahoe officially on the map. Ironically, Fremont’s original mapping errors eventually led to the accidental partitioning of Lake Tahoe—one third in Nevada, two thirds in California—leaving Tahoe split between the Golden State and the Silver State in perpetuity.

Photo by Phillip and Jean Earl, and Richard Lane from the University of Nevada, Reno Special Collections department

American Conservation Movement Has Roots in Tahoe Territory

The patchwork of governmental jurisdictions that eventually formed here—comprising two states, five counties, and one city—has long made conservation efforts here complex. Yet despite these challenges (or because of them) the American Conservation Movement has deep roots right here in Tahoe territory. By the late 1880s, more than one billion board feet of old-growth timber had already been stripped from the Basin—eventually forcing Tahoe’s major timber companies to literally pack up their sawmills and move elsewhere. With close proximity to the new transcontinental railroad near Truckee, industrial fishing methods soon brought Tahoe’s famous Lahontan cuthroat trout to the brink of extinction (the first major American fishery to collapse). By 1888, when an aging former-mountaineer named John Muir finally showed up at Lake Tahoe for a long-delayed vacation, the devastation he witnessed spurred him to form the Sierra Club—and to lobby hard for the creation of the new National Parks and Forest Reserves. Ironically, Muir failed in repeated attempts to create a Tahoe National Park. Yet the creation of the new Tahoe National Forest Reserve (stretching all the way south toward Yosemite) was a consolation prize worth celebrating.

Based in part on Muir’s efforts, Tahoe’s devastated forests gradually recovered—along with a booming tourist trade. Lavish new resorts like the legendary Tahoe Tavern were soon competing for business with Lucky Baldwin’s Tallac Hotel and Casino—linked by a system of equally luxurious little steamships and railroads that brought a continuous flood of wealthy tourists each summer to the Lake. By the 1920s, however, travel by rail and steamship was rapidly being replaced by the automobile—and middle-class resorts catering to motorized tourists sprang up like mushrooms, bringing famous authors like John Steinbeck and Bertrand Russell (both future Nobel Prize winners) for extended sojourns at the Lake.

Sleepy Lake Tahoe Towns Spurred to Tremendous Growth

After 1950, year-round auto access gradually transformed sleepy Lake Tahoe towns into a booming four-season resort mecca. By 1960, Walt Disney helped to launch the first nationally-televised Olympic Games from Squaw Valley—and Tahoe entered an unprecedented new era of unbridled economic growth and breakneck land development.

One (unintended) trigger to Tahoe’s tremendous growth was a 1954 federal law effectively banning slot machines nationwide—except in Nevada. With casinos in Los Angeles and San Francisco suddenly shut down, eager gamblers starved for excitement had little choice but to jump in their cars and head to Las Vegas or Reno. To tempt these streams of gamblers to stay and play, Tahoe’s once-sleepy little state line border communities suddenly witnessed the construction of enormous new high-rise casino towers as torrents of free-spending travelers poured toward the Lake.

Hence by the early 1960s architects had sketched out plans for a city the size of San Francisco ringing Tahoe’s shores. Highway planners proposed four-lane freeways ringing the lakeshore and a concrete bridge spanning Emerald Bay. Wetlands that naturally filtered Tahoe’s waters were paved over to build airport runways or dredged to create marinas. Gridlock and smog became inescapable. Tahoe was transformed on a scale its earliest pioneers could not possibly have imagined.

But other forces were at work at the Lake as well. Since the 1930s, for example, one of Tahoe’s wealthiest residents, Colonel Max Fleischmann—heir to the massive Fleischmann’s Yeast fortune, and a lifelong conservationist—had worked closely with his friend Lester Summerfield (a Reno attorney widely known as Nevada’s “Mr. Republican”) to bring both California and Nevada to the table in order to reign in the chaotic growth they saw as a threat to the Lake. After 1951, the Fleischmann Foundation under Summerfield’s leadership continued to champion conservation causes. By 1961, with the Nevada Department of Health forecasting an “average of 30 million gallons of sewage per day and at times 50 million” spilling into the Lake, Summerfield and the Fleischmann Foundation demanded that the Washoe County Planning Commission delay approval of the new Incline Village development package on the north shore. Warning grimly that the federal government might soon have to step in “to prevent a national tragedy,” California’s Governor Pat Brown eventually helped to broker a long-range plan calling for the transportation of all treated sewage from the Basin. In 1969, under the leadership of then-California Governor Ronald Reagan and Nevada Governor Paul Laxalt, a bi-state, bipartisan compact between California and Nevada was finally ratified by the U.S. Congress. By 1971, a system of pipelines for exporting Tahoe’s effluents completely outside the Basin was largely completed, and the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency had been formed.

Our thanks to Tahoe Beneath the Surface author, Scott Lankford, Ph.D. for significant contribution to our understanding of Lake Tahoe’s history. Dr. Lankford is Professor of English at the Foothill Center for a Sustainable Future, Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California.

His published works include:

Tahoe Beneath the Surface: The Hidden History of the World’s Largest Mountain Lake, October 2010

– Bronze Medal as 2010 Nature Book of the Year by Foreword Magazine

Northwest Passages: From the Pen of John Muir, Revised 1998

– Benjamin Franklin Prize, Independent Publishers Association